Kiyomi Iwata, who was born in Kobe, Japan, is a textile artist whose work explores the relationship between geographies—East and West, North and South— through cultural signifiers, text, and materiality. After immigrating to the United States in 1961 and marrying, Iwata studied at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, where she was introduced to batik dyeing, and the Penland School of Craft. In the 1970s, she and her family relocated to New York City, where she studied at the New School for Social Research and the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. During those years, she began fashioning silk organza into serial boxes, which she describes as “container[s] of mystery.” Iwata’s career blossomed in the 1980s, but after 9/11, her work changed from subtle concepts to direct communication, taking the form of fabric scrolls with handwritten haiku and waka poems. After returning to Richmond in 2010, she began another body of work made from kibiso, a trademarked thread provided by Tsuruoka Fabric Industry Cooperative in Tsuruoka, Japan. In these wall hangings, which consist of linear elements made from woven kibiso covered in gold leaf, Iwata exchanges forms for their absence.

Amanda Dalla Villa Adams: You were born during World War II and grew up during the American occupation and rebuilding of Japan. How, if at all, do you see those early experiences in your work?

Kiyomi Iwata: After the war, the whole nation was working hard to recover and rebuild. If I could identify this time by a color, it would be gray—not warm gray, but dirty gray. However, there was one bright spot during this period for a restless young woman, and it was Hollywood movies. Everybody on the screen seemed happy and lighthearted under the sunny California sky.

I was born and raised in Kobe, which is a narrow city with mountains on the north side and the sea on the south side. Kobe has a very busy seaport, and many foreign ships would come and go, which made many young people long to hop on a ship and sail around the world. I was not the only one who felt restless then. Many of my peers were heading to the United States to study—some seriously pursued an education, but many went to “study English,” which meant seeking adventures.

I had a double citizenship because my father was born in the United States. During this period, people with dual citizenship had to choose a country by the time they reached the age of 18. I chose the United States and boarded an airplane from Haneda Airport. My destination was not California, but Washington, DC, where my father’s sister lived. I enrolled at a local university to study English, but studying was not exactly my top priority. Then came the mating game, and I married my husband. When he was hired by a large corporation located outside Richmond, Virginia, we moved to the South.

I went to studio classes at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts to study art, which I had always enjoyed. I took many basic courses, including drawing and painting, but when I took a batik class it changed my life. First, apply hot wax on the fabric, then immerse the fabric into cold dye, pull out it from the pot, and the fabric changes its whole character with brilliant colors, except where it was covered with the wax. What a gratifying experience—I knew I wanted to work with textiles for a long time.

ADVA: How did you gain exposure for your work? What did your earliest pieces look like?

KI: In 1973, together with my husband and two small children, I moved to New York City. I tried to live in a Greenwich Village apartment, but it did not take long to realize that I was not as hip as I thought. We retreated to Nyack, New York, where we bought a large old house. As soon as we moved to New York City, I enrolled at the New School for Social Research, where Françoise Grossen was teaching. She was making huge rope sculptures using the seemingly simple technique of knotting.

It was a gratifying time for me because I met very generous and talented people involved in the creative endeavor. Grossen taught me the attitude toward creating artwork. Curator, art historian, and writer Mildred Constantine was always generous with her suggestions, and she shared the importance of using the right words. Most of all I learned from her how to live. Jack Lenor Larsen also offered wise counsel and opened doors for me. I learned from him that “if one thinks it is good enough, consider it a good start,” which still echoes in my mind.

The art scene in New York was stimulating because people came with big dreams, and it was exciting to be around dreamers. In order to have a solo show, I joined a cooperative gallery in SoHo, which offered a beautiful space. It was during this time that the silk organza work evolved into a small silk box—almost like the essence of what I had been doing. The silk box is small, intimate, and the viewer must come close to interact. It is a container of mystery.

ADVA: You have said that “having a family was an equally creative thing to do, but the gratification came in a longer range.” What do you mean? Did you feel pressure to make a choice between your two daughters and art?

KI: Combining the art environment and the raising of small children was not easy. Fortunately, there was a community of mothers who were in the same situation. We took care of each other’s children. I am not sure that having children is a good idea professionally; they are time consuming, energy consuming, and expensive. On the other hand, it was an experience I would have hated to miss—although when I was going through it, I was less sentimental. There are many experiences in life that one appreciates only years later when one looks back, and raising children is one of them.

ADVA: After 9/11, you began making scrolls that incorporate 18th-century Japanese waka (or tanka), haiku, and other short poems. Why did you begin making this type of work?

KI: 9/11 was a gorgeous day. I had been walking along the Hudson River with a friend and hopped back into my car to head home. The radio announced the surreal news that an airplane had crashed into the World Trade Center. The whole idea was so outrageous that I expected Godzilla, the famous Japanese monster, to pop up at the top of the World Trade Center. Reality set in, with people jumping off the building, and the sense of security and a comfortable life was gone. Everything previously unimaginable was possible.

I wanted to communicate directly how I felt. Gone were the subtle wabi-sabi works. The long scrolls I made during this time were written with haiku and waka—first in English translations, then I wrote directly in Japanese haiku. Eventually I preferred not to be legible, and writing in Japanese became more of a design. The waka I chose to write were very fatalistic, which is a traditional Japanese sensitivity. They are all written in gold on a gold surface; unless the light hits at a certain angle, they are not legible. Perhaps Japanese poems are more fatalistic than Western forms because Japan is a small island nation surrounded by ocean. There are typhoons, floods, and tsunamis every year. People learn to live with nature. In Western culture, on the other hand, people thought to control nature because they did not have so many natural calamities—until recently with global warming.

ADVA: You moved back to Richmond in 2010, and in 2015, the Visual Arts Center (VisArts) mounted a retrospective of your work, “From Volume to Line,” which covered more than three decades. Even though your career began in the 1980s and you were awarded an NEA grant in 1986, it seems like you only really received recognition as an older adult. Can you comment on this?

KI: I feel lucky that we live in an age when a woman can take good care of herself, free from domestic obligations and free to pursue full time what interests her. Still, it is a fact that even though I was involved in my work, my professional life took off 100 percent when the last child left home for college. I was young enough and energetic enough then, which made the issue of age somewhat less important. Each stage of life comes with pros and cons. The good news at this stage of my life is that my head is much clearer in terms of what I like to do. It is not muddled with the issues of youth. I am not discrediting youth, though. It is wonderful to be young and have a full life ahead of you.

ADVA: When you returned to Richmond, you began using kibiso, the rough fiber made from the waste left over when silk is pulled from a cocoon, and ogarami choshi, the silk thread remaining on the bobbin at the end of production. Why did you choose these materials?

KI: During my annual trip to Tokyo, an acquaintance introduced me to kibiso, which is the beginning of the silkworm’s production. The silkworms produce 3,000 meters of thread during their lifetime, and kibiso is the very first 10 meters. It is rough and coarse and was discarded in the past. With the Green Movement, silk manufacturers decided to see if there was a market for this thread. It was given to artists and designers to play with, and it became one of the most sought-after threads in Japan.

Kibiso has a very different attraction for me, contrary to my usual silk organza, which is woven from fine silk thread. By using kibiso, I am using the silkworm’s whole life output, which is gratifying. I went back to the traditional manner of using thread to weave. Whatever the thread had from its previous life, such as the silkworm’s cocoon, I left it where it was and dyed the thread. Ogarami choshi is also a remnant of silk factory production. It is the leftover thread on a bobbin, and in order to reuse the bobbin, a factory worker cuts it off. I use the ogarami choshi as is, too.

ADVA: You sometimes make box-like forms and sculptures that use furoshiki, a traditional Japanese wrapping of containers. Furoshiki began during the Nara period and was connected to religious goods given at temples. Does your work incorporate that religious and/or spiritual connection?

KI: I started to wonder if I could reverse the surface of the object from silk to a dominant hard metal with a soft silk finish such as one sees in 18th-century Japanese armor. The surface of the armor is hard, but every inch of it is embellished with beautifully dyed silk fabric and threads. One year I went to Yaddo to explore this possibility, and the “Fold” series was created. I used copper, brass, and aluminum mesh. Contrary to my previous work, this series was heavily embellished with metal leaf, French embroidery knots, some knotted silk tubes, and more.Furoshiki, the traditional Japanese way of wrapping an important gift, seemed an appropriate form. One cannot see the contents of a gift wrapped in furoshiki—it is hidden until one opens the cloth. The “Fold” pieces were all tied at the center, and you could not see the interior; although many times, a waka was written inside with gold leaf. The quality of mystery has always intrigued me.

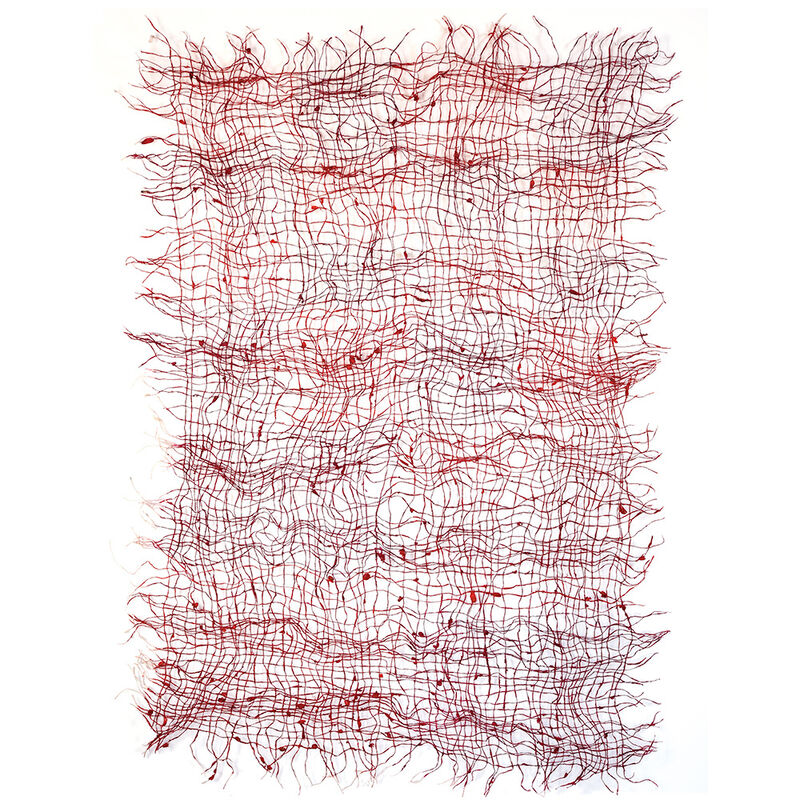

ADVA: Since 2010, you have been making delicate, woven wall hangings that resemble grids or maps. They appear to be fragments, and there is an unfinished quality to them. Some are large and freeform, while others are intimate and marked off by a frame. Can you explain the motivation behind these works as well as the reason for their variety?

KI: My recent work originated when I crossed the Mason-Dixon line to move back to the South. Although I had lived in Richmond decades ago, I was new to the country then and not aware of the complex nuance of North versus South. After living in the United States for over half a century, I see the difference now. Whether consciously or not, that difference must be reflected in my new works. Some are very clearly divided into two parts, as in Southern Crossing Six, which has weaving with silver leaf on top and indigo weaving at the bottom to create two visual parts.

I don’t try to make the creative process a mystery, but in a way it is. In the last decade, I have been working with woven kibiso made into tapestry-like hangings. They are either dyed or embellished with gold leaf, and I enjoy the process as much as the results. The whole idea of working, using hands and mind, and letting the process lead me is an eternal moment of joy for me. Sometimes I use a frame to give the piece a limitation, and other times I let the wall space frame the piece. It really is a difference in how I like to present the piece.

.

ADVA: Much has been said about how your work navigates dualities like East and West. Do you agree with this interpretation?

KI: It is true that my aesthetic sense comes from East and West, more obviously in some cases than in others. I enjoyed viewing Eva Hesse’s work, which speaks directly to me, although it is a very Western sensitivity and belongs to the abject rather than the obviously beautiful; it is more feminine compared to other Minimal works that I enjoy and understand. I prefer understatement to full explanation. The quality of the unsaid is much more intriguing than having everything spelled out.