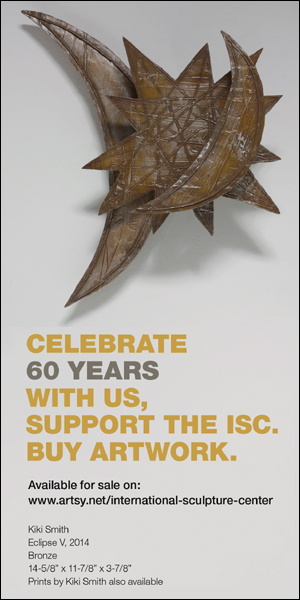

Hiroshi Sugimoto makes little distinction between the two- and three-dimensional. Photography, sculpture, and architecture are all part of his project to find “a creation of human consciousness.” The long-exposure images of seascapes, abandoned movie theaters, and natural history dioramas for which he is best known carry as much weight as any freestanding object and reveal a deep understanding of scale and space—the same qualities that characterize his quintessentially Modernist forms derived from mathematical formulae. He considers works such as Onduloid, A surface of Revolution with Constant Non-Zero Mean Curvature (2006), Hypersphere: Constant Curvature Surface Revolution of Hyperbolic Type (2012), and Surface of Revolution with Constant Negative Curvature (2006) not as sculptures but as representations of scientific endeavor, or “models.”

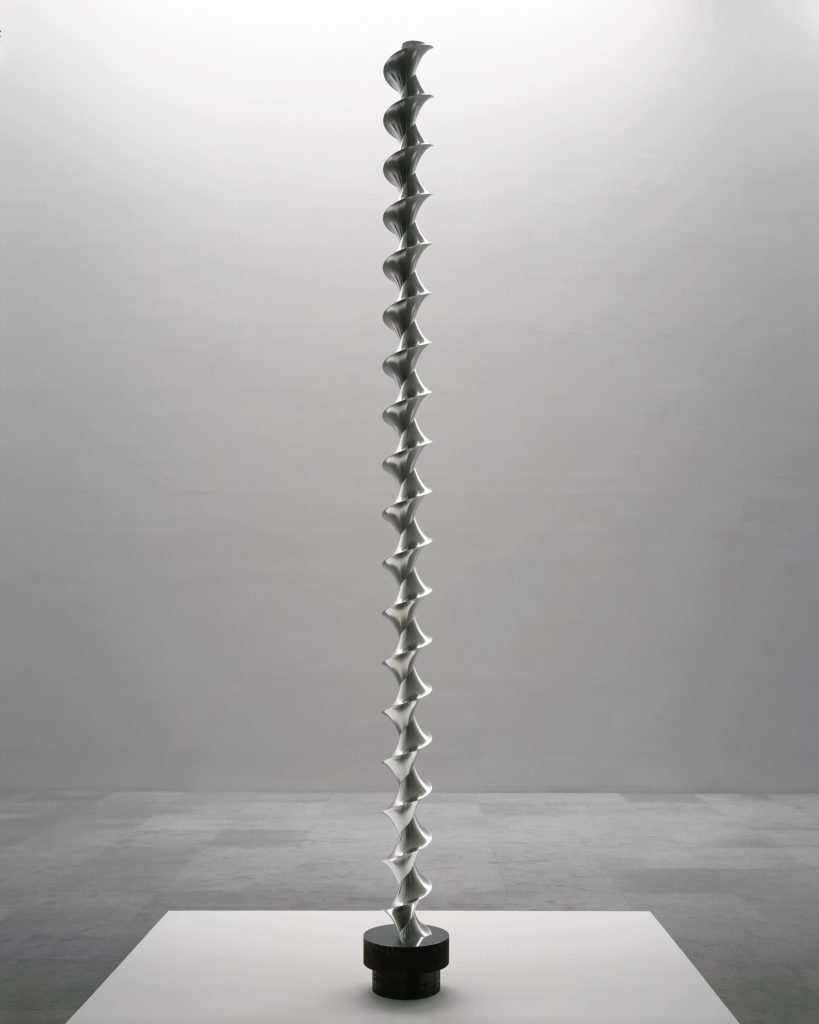

Point of Infinity: Surface of Revolution with Constant Negative Curvature (2023; Yerba Buena Island, San Francisco), Sugimoto’s first permanent public art commission, transforms one of those “models” into a monumental example of his endeavor to see architecture as a means of realizing the real. Just as his immeasurable seascapes reach for a boundless horizon, this carefully positioned form, rising 21 meters from the ground to its sky-piercing tip, reaches into a limitless expanse, expanding and contracting its surroundings and engaging viewers in an environment of perceptual challenge.

Rajesh Punj: “Time Machine,” your recent survey exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London, featured a smaller version of Point of Infinity: Surface of Revolution with Constant Negative Curvature.

Hiroshi Sugimoto: The one in the exhibition was the point of reference for the larger work in the United States.

RP: You refer to the smaller works as “models,” and the major work in San Francisco as architecture.

HS: Point of Infinity is on an architectural scale but originally born of a model. I don’t use the word “sculpture,” because I don’t call myself a “sculptor.”

RP: You are primarily known as a photographer. Have you always had this architectural interest?

HS: Yes, I became an architect as well, and I established my architectural company, New Material Research Laboratory (NMRL), in Tokyo in 2008. The company worked on the project for San Francisco. As an artist, when thinking architecturally, I don’t change the way I work.

RP: So physical form is much like the photographic for you?

HS: Yes. I don’t see any difference between the two- and three-dimensional; everything is decided by one’s imagination. It comes to my mind either as a three-dimensional form or as a photograph.

RP: Do you see your photographs as physical in a sense?

HS: Photographs pause physicality. Depression photography is a representation of one kind of reality; in my case, I am projecting the image onto a different surface. I never go outside and shoot what I find, or find something to shoot. I recompose what I already have in my mind by making it happen in this world, and now I want to make it happen in three-dimensional shapes. Like a sculpture, but not a sculpture—that’s my motto.

RP: How do you feel about the scale and location of Point of Infinity in San Francisco?

HS: Making it 21 meters high proved a technical challenge. There was the question of how to deliver it accurately and within budget, which was the most difficult part.

RP: Were you conscious of the landscape, of the sky, of the space occupied by your work? I remember you telling me about how for years you would locate yourself at a specific point to photograph the same scene for hours at a time. You seemed to be impressing yourself on the landscape in the same way as your architectural work is now.

HS: I seriously considered how my “mathematical model” would fit in the landscape. Standing at that particular point of Yerba Buena Island, looking out onto the San Francisco Bay skyline, it appeared very sculptural. So, we had to carefully compose how it would be seen from the viewing platform against a background of the Golden Gate Bridge—the model representing the architecture, the architectural work an enlargement of the model, each echoing the other. The surrounding park becomes an interesting point of view for the work, and I wanted it to touch the sky.

RP: You can see Infinity Point from quite some distance as well.

HS: Even from the city, you can see a tiny triangular shape, especially at sunset, as the stainless steel shines beyond itself.

RP: Are you working on other architectural-scale projects at the moment? I know that you redesigned the lobby of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, creating an immersive synthesis of sculpture, furniture, and conceptual art.

HS: I have mathematical models in mind that could become something more monumental. We have a major project going on at the Hirshhorn right now, a new design for the sculpture garden. The plan had to be confirmed with the U.S. government before construction. There was a long debate for four years, with many people wanting to protect a landmark building. Essentially, conservatives do not wish to see any kind of change. In the end, I had to give up 10 percent of our original plan.

RP: Surface of Revolution with Constant Negative Curvature (2006), the Point of Infinity model, dates to 2006.

HS: It was first shown at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, together with a Brancusi sculpture.

RP: Is Brancusi an artist you have always looked at?

HS: Yes, I have always admired his sculptures, the simplicity of them. Brancusi’s work was entirely sculptural, mine is more formulaic; it has a trigonometric function. I have only to set it up, and then it manifests as a beautiful sculpture, which I feel is sometimes more beautiful than the human mind can create. Mathematics is able to explain nature better than we can represent it since nature comes well before our artistic minds. Natural elements create a well-balanced beauty that we seek to represent. I think that art comes as a consequence of nature’s intervention. Everything is probably of the same roots, deep and mysterious. There is an incredible energy to the universe, as there is behind the human mind.

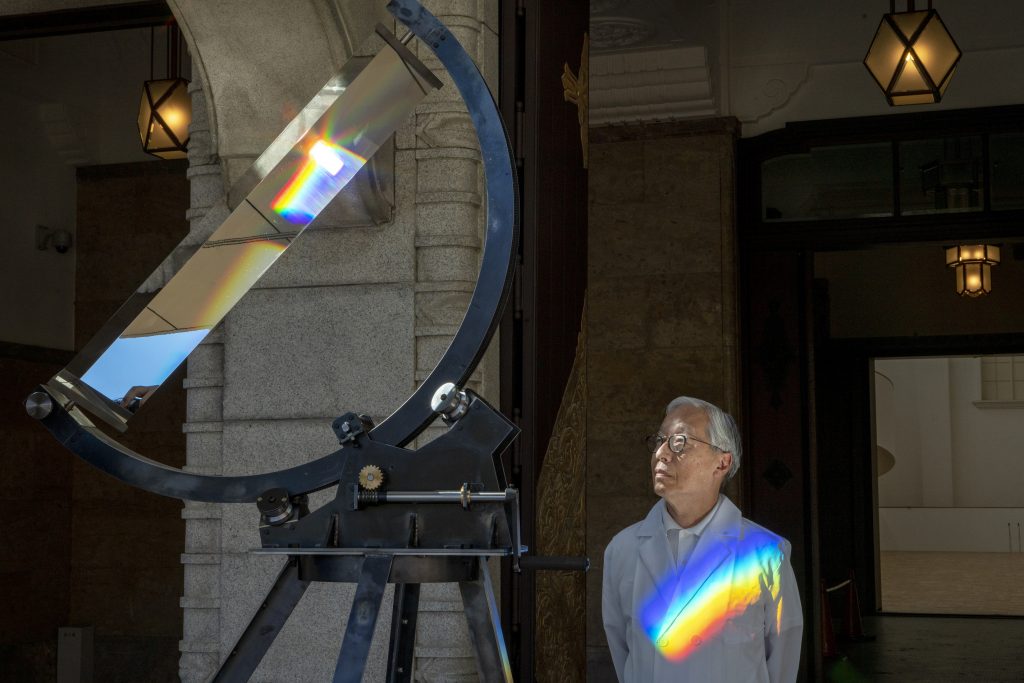

RP: I once asked you about your understanding of beauty, and you said “that when I hear a piece of music, it’s the note that drops, that offers a kind of imperfection, that is fundamental to our understanding of beauty.” Is the idea of imperfection important to you? How does that intersect with science and mathematics, for instance in your “Opticks” series born of Polaroid prints?

HS: There are quite a few of these prints, in limited numbers, unique almost. Like the original designs and drawings for Infinity Point, they were influenced by my discovery of Isaac Newton’s optical experiments. I found and purchased an original edition of his Opticks: or, A treatise of the reflections, refractions, inflexions and colours of light (1704), published in English, at auction. It’s a very important work that changed the scientific world and how we understand the nature of light.

RP: For you, it’s then about applying those ideas.

HS: I wanted the work to be influenced by Newton’s experience. So, I introduced a prism, of much higher quality than in Newton’s time, and created an east-facing room in my Tokyo studio based on the “separatism” study. The sun comes up and hits the prism, stretching into the corner, and I had mirrors made to reflect all of the refracted colors into the dark space so I could see them better. And then I decided to enter the space itself. It sounds easy, but it wasn’t, and I’m probably the first photographer to try and capture colored light in this way. Usually, photographers are looking for shapes in the world, but I’m attempting to bypass the shape and concentrate on the light itself. I want to be in harmony with nature and not compete with it. I’m very pleased with the works.

RP: They are almost painterly and immensely beautiful. There is an incredible sense of depth to many of the colors.

HS: The colors don’t emerge from a flat surface. It’s really about the depth of currents. A painter paints onto canvas, but in my case, the colors create themselves. So, you see the depth and layers of overlapping, and in that sense, they are almost painterly photographs. Paint speaks as paint; it’s a solid material. I stopped at the surface but still delivered something more intense.

RP: Certain other colors appear more impenetrable, remaining entirely two-dimensional.

HS: Each has its psychological gate. Following Newton, I discovered their characteristics.

RP: Do the individual works offer something different?

HS: They demand much of the viewer. I don’t want to say, “This is how you should see each of the works”; it is for you to feel which color is the most intriguing—in between “blue and green” introduces an indescribable space.

RP: Are The Theory of Colours works part of the “Opticks” series?

HS: Yes, I have only shown a small portion. I was working between my New York and Tokyo studios. In Japan, in my studio facing to the east, I work with the morning light; and in New York, I have the sunset in the afternoon, introducing a vastness to the works.

RP: Light is just as significant to Infinity Point. Has light played a fundamental role in how you see and how you’ve approached your work over the course of your career?

HS: Yes, it has interest for a lifetime.

RP: I’m fascinated by the “mathematical models” that you refrain from calling sculptures.

HS: The depth is something that amazes me in many of the works, the sense of their having a simultaneous meaning and meaninglessness to them.

RP: How involved are you with the architectural activities of your firm?

HS: I decide if I want to be involved or not. NMRL takes on many projects, including the interior of a new hotel in Kyoto, while I have been working on the sculpture garden. This has all led to building my foundation in Japan, which has become my most important architectural project of all. It is two and a half acres facing the ocean.

Point of Infinity: Surface of Revolution with Constant Negative Curvature is on view on Yerba Buena Island in San Francisco. “Optical Allusion,” an exhibition devoted to Sugimoto’s Opticks prints, is on view at Lisson Gallery, London, through August 2, 2024.